Our children spend six and a half hours a day in school. For those who are not mathematically inclined, that’s over thirty hours a week. That is a lot of time to be learning and growing and evolving without parents truly knowing the specifics of what happened in the day. And yet, we are often left wondering how we can do more at home, and support what is being taught. Are they grasping concepts? With the learning lag of online school still very much at the forefront, many parents are worried that they need to provide extra attention to learning, These questions are magnified by not really knowing what our children are doing during the day. What ARE they learning? What concepts are being covered? When the typical response to “what did you learn today” is either “I don’t know” or “stuff”, how can you even be effective?

As a teacher, one of the most frequently asked questions is how to support children at home. Let it be said that I definitely don’t have all the answers. I do know that parents typically fall into one of two categories; those who are over-involved and those who are under-involved. Why is that the case? Because as we know with everything else in life, striking a balance is next to impossible. So why should supporting our children’s education be anything different?

Instead, we inherently swing towards one of the extremes and wonder how to ease off the gas a bit more. I wanted to provide some basic tips and tricks for how to support children. These are things that teachers wish parents knew, and are easy to implement. The best part is that you don’t need to know what concepts are being covered to start!

Everything starts at home, the night before. We have all heard of the importance of a good night’s sleep and I’m sure that many of you have bedtime routines down pat at this point… I’m certain more so for parental sanity than well-rested children wink. What I am referring to is before bedtime. In an effort to engage our children, many of them are over-programmed. Extra-curricular activities are important, don’t get me wrong. However, having a different activity every night of the week is a LOT. Every child is different, and where some can handle only one activity per week, others may be able to handle more. It’s important to remember that having multiple commitments can cause anxiety in children. I have had many conversations with students who have said they are unable to complete things at home or feel that they have too much going on because they have activities almost every day. This is a prime example of the importance of open dialogue between children and parents. This is not to say that the child who does not want to practice piano (cough cough my own child) gets to opt-out, but we do discuss the number of weekly commitments together.

The use of an agenda is a fabulous tool. When our children are young, they are a great way to communicate with the teacher or vice versa. This helps to cut down on the unknowns of the day. When children are older, it is a great time-management tool. Unfortunately, many schools have paused the use of agendas due to Covid, as they try to minimize the items going back and forth from school. If you already have an agenda system in place, make sure to use it, and model for older children (grades 3+) how it can be helpful. Reviewing the agenda daily, and initialling it so that teacher can see you have read it is an easy start. If there is no agenda system in place, reach out to the homeroom teacher and see what the best form of communication is for weekly reminders, special days and upcoming assignments and assessments. This may look like a virtual newsletter, an email system, or even a virtual classroom. Don’t leave it to your child to tell you where to find the day-to-day information. That being said, no matter what the system, please do not expect the teacher to record verbatim what has happened in the day, as that is just not feasible.

Reading at home is so important. This can be a bit of a no-brainer in theory but can be difficult to tackle in practice. When our kids are younger, we often read together with them; help them sound out the words or look for picture clues. As children get older and are more independent, parents do not always know the books they are reading (I mean, has anyone really had the time to pick up the most recent DogMan book??). This begs the question – how do you support reading? The good news for parents is that as students enter the end of primary and into junior grades, reading is more about explaining your understanding and less about your oral fluency. Talking about reading at home is the number one tip I give all parents of the students I teach. This means we need to talk about reading with our children, and always encourage them to support their thinking. These mini conversations can take place in the car on the way to school, at the dinner table, or right before bed. They do not have to be formal assessments.

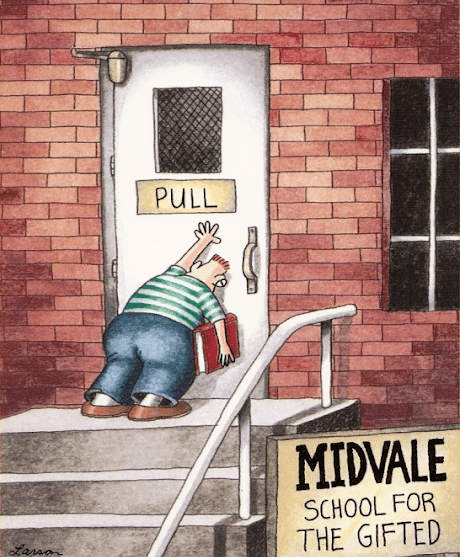

Simply ask what their favourite part is so far, what they think is going to happen next, or which character is they can relate to the best and then ask WHY. This is an area of need for all children (and especially gifted thinkers). Encouraging children to give more than a one-word answer, and think about supporting their thinking will give them a leg-up not just in literacy but in all subjects. I recognize that this assumes our children actually read at home, which I know many do not. The good news is that these conversations can be about any subject (space, chocolate cake, or Pokemon) – the key is in the WHY.

The last point I want to cover is to ask children how they are feeling. This year, more so than others, brings with it a lot of anxiety. Whether children are back in the class, still online, or back and forth, there are a multitude of feelings. Taking time to ask children how they are doing, and giving them both the tools and the outlets to truly express it are imperative. I can tell you that 99% of children will not just walk up to a parent and articulate perfectly how they are feeling (nor would 99% of adults for that matter). Asking children to journal, mindmap, or colour a picture of their day are all ways that can help you understand how they are doing without a formal conversation. Check-ins will help gauge how they are doing with all the changes and uncertainty of the year. Just as our mental health is important, so is theirs. As they cannot necessarily advocate for themselves it is our job to ask questions to help them process. If there is interest, I can definitely go into this more in a later post.

The only thing you definitely cannot do is read minds. Although we may want to, we cannot be flies on the wall in the classroom. Even as a 4th-grade teacher with a child in a grade 4 classroom, I STILL don’t know what she is doing on the daily. We all struggle with this. We will never know exactly what happened in the day but we can try to give children some tools to help them get through, And trust me, your child’s teacher will thank you. I know I would.

This is life. Love, Mom.