A couple of weeks ago, I went out with two girlfriends who are also teachers. So, of course, at one point the conversation inevitably turned to the profession. The gist of the conversation, and how heated we got when we talked, is what influenced this post.

Let me start by saying that every job has its ups and downs. Every profession has positive elements and those that are less desirable. And, at one point or another, we have all complained about our jobs. Teachers, however, have somehow earned the medal of “top complainers”. The general consensus is that teachers have nothing to complain about. Summers off, short hours, good pay, and benefits, a bull of a union…. what do we have to be upset about? If that is the case, why are teachers taking more than fifty percent more sick days than a decade ago? Why have mental health leaves skyrocketed? And why is teacher burnout a such common conversation nowadays?

Teachers used to just teach. I don’t know about you, but when we were in school, the teacher stood at the front of the class, taught a lesson, and then assigned follow-up work – questions from a textbook, a worksheet, or something similar. I remember the thirty minutes of DEAR (Drop Everything And Read) time every morning.

My music teacher used to play his accordion at the front of the class while we sat at our desks and sang along. I can still hear the sound of the AV cart rolling down the hall so we could watch Bill Nye videos for science. Granted, as kids, we didn’t have a good understanding of what the teacher did after hours (I mean, who didn’t think their teacher slept at the school?). I’m not saying teachers didn’t work hard, because I am sure they did, but the expectations were much different than they are today.

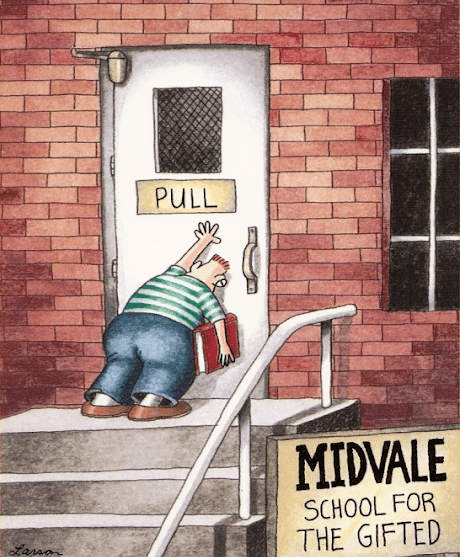

The curriculum of today looks very different than it did a decade ago. The expectations are more rigorous and robust. This provides a much more enriching curriculum for students. However, since there is so much to cover, the understanding is that everything must have a purpose, and be tied into the curriculum. The days of DEAR are gone. Often teachers are told that if there is no follow-up or assessment component, it can’t be done. Reading for the love of it or watching a video to enjoy the content isn’t enough anymore. There must be a specific, curriculum-driven purpose to everything. Now, I don’t necessarily disagree with the thinking behind this. I think that if you cannot justify why you are filling your time with a particular lesson, it may not have a place in the day. Equally, just as in any profession, there are teachers who, if not monitored, would otherwise take advantage of this. And the truth is, with so much curriculum to cover there is very little wiggle room in the day to begin with. But in an effort to enrich the day, we run the risk of removing the love of learning and exploring. For example, there is a true benefit to reading for enjoyment, without worrying that you are going to be assessed on what you are doing. Sadly many students wouldn’t otherwise pick up a book if it was not during school hours. Teachers have very little leeway to exercise these options. Which is all to assume that they understand the options in front of them. Teachers college is fraught with hypotheticals, academic articles and educational history. The academic nature of the programs puts teachers at a huge disservice. When I completed my degree I had three years of once-a-week practicum, and I definitely wasn’t prepared. Teachers now have even less. There is not enough real-world experience to adequately prepare new teachers for their roles.

If that was all, the job would already be stressful. However, this is only part of the equation. As a teacher today, delivering curriculum is only a component of your job. You are also a social worker, tech support personnel, therapist, confidant, substitute parent and parenting advisor. You can even, at times be a marriage counsellor, verbal punching bag, psychologist, or suicide support interventionist. You have not been trained to do any of these jobs properly, but are expected to put any of those hats on at a moment’s notice (and sometimes more than one simultaneously). Nothing in the system prepares teachers for those roles. Some professionals go to school for years to do these jobs properly. However, in our tapped system they are only available infrequently, and rarely at the moment when they are needed most. Most training and professional development are done during monthly staff meetings, or on teachers’ own time. Courses and training are often offered on a voluntary basis for teachers to complete on their own. The argument from society is that it is part of the job and teachers just have to do it. The argument from the teachers union is it isn’t part of the job and teachers have to say no. Neither one is feasible and there is very little middle ground. Teachers are so many things to so many people. It is rewarding but exhausting.

Many teachers take their jobs home with them both emotionally and physically. Yes, teachers are allocated a certain amount of prep time in the day, but that is often used to prepare engaging lessons, soothe a student, handle a social disagreement from recess, or phone a parent. Paperwork, report cards (at a time cost of over an hour per student), marking, timely assessment and feedback, and planning are all often taken home in the evening in an effort to catch up.

None of this is part of the workday. And yes, I am well aware that other professions work after hours. This is a typical counter-argument to teacher concerns. However, they are typically paid for their overtime or paid per project. Granted there are other professions where work is taken home to be completed without overtime, but just because others do it doesn’t make it okay for anyone.

Taking all of this into account, of course there would be burnout. It only makes sense that all the pressure would become too much for some. I myself fell victim to the pressure pre-covid. A few years ago, I was presented with a class that was like no other. Individually they required inordinate support, much more than I could provide them as one person. Together, their personalities did not mix well. A CYW (child and youth worker) was placed in my classroom for daily support. Together we created a multitude of social skills lessons, which unfortunately did very little to support the class. I felt like an octopus, trying to put out multiple fires at the same time. This was all before I even attempted the curriculum (which many days went right out the window). I began having panic attacks before the students even walked in the door. I would sit in my vice principal’s office and cry out of sheer frustration. I became anxious at school and home. The work-life balance was obliterated. My diminished mental health made it impossible for me to do my job as a teacher AND as a mother. So with the help of my admin and my doctor, I made the decision to take a stress leave. My steps to protect my mental health was the best decision I could have made. It was also the beginning of my journey of self-care advocacy for myself and others.

I share this because I am a seasoned teacher. I would like to think that I can take most of what the profession throws at me. But at a point in time, it was all too much for me to handle. In the spirit of transparency, even as I reread this post to review it before publishing, I feel tears in my eyes. The stress and toll can, at times, be too much. New teachers who don’t have the experience, and older teachers who have difficulty adapting to the changing landscape of the system are even more at risk. There is real merit to teachers asking for help…. to advocating for more support. Teachers are crying out for more support for their students, their classrooms, and themselves. The system is not build to adequately accomplish this. There is not enough money, time, or hours in the day. There is no easy answer here. It is a systemic issue that will not be fixed overnight.

This post is not meant to be a “woe is me” rant. It isn’t meant to have others feel sorry for teachers. I am sharing this for those who believe that teachers simply deliver the curriculum, go home at night with a glass of wine, and then enjoy summers off. I am sharing for those who believe that all teachers do is complain, and have no merit to do so. This is especially important as we are set to enter another unprecedented year in the education system. So next time you feel yourself judging a teacher for having the summers off, having an “easy” job, or for complaining too much, I urge you to take a second to think that through.

This is life. Love, Mom.